What does an Urban Watershed Framework Plan look like? The Plan shows how repair of degraded urban watersheds can be a powerful agent for reinventing the neighborhood environments of post-industrial cities. Most urban waterbodies are unsafe for swimming, fishing, and as sources of drinking water due to anthropogenic activity. Urban riparian corridors often exhibit “urban stream syndrome” where excessive water and sediment flows lead to flooding, erosion, ecosystem depletion, and extensive property damage. Considering that city and watershed generate conflicting shape and structure across the landscape, how can neighborhood form fix the watershed to deliver ecosystem services?

The Plan pioneers an innovative developmental vocabulary for universal application in “wet” cities, showing what a comprehensive design-based urban watershed plan looks like. The Plan introduces watershed management principles into both high-density and low-density neighborhood design for a fast-growing city with severe water management problems. The project invents a transferable planning vocabulary aligning the city’s metabolism with that of the watershed, recognizing that the greatest ongoing challenge in planning is design within human-dominated ecosystems. A portfolio of modulated green infrastructural retrofits at the neighborhood scale provides gain-of-function in conventional infrastructure systems. Green infrastructure, incorporating new urban 'rain terrains' (holding water) and improving 'riparian networks' (draining water), delivers ecosystem services benchmarked to the Ecosystem Services Concept (ESC). ESC is a matrix of the 17 ecological services delivered by all healthy ecosystems including regulation of flooding and water pollution and should be a benchmark in evaluating future neighborhood design.

Ecological problems are social problems. Reconciliation of neighborhood and watershed functioning enhance livability and place-based economic development, while improving community resilience to the shocks attending volatile weather patterns. Streets and parking lots can be ecological assets rather than liabilities, while “rewilded” neighborhood landscapes offer new types of recreational and social scenes. Most importantly, an urban watershed vocabulary creates new regenerative civic landscapes that produce enduring ecosystem value and express new levels of 'commoning'—an intrinsically grassroots form of natural resource stewardship beyond public sector mandates.

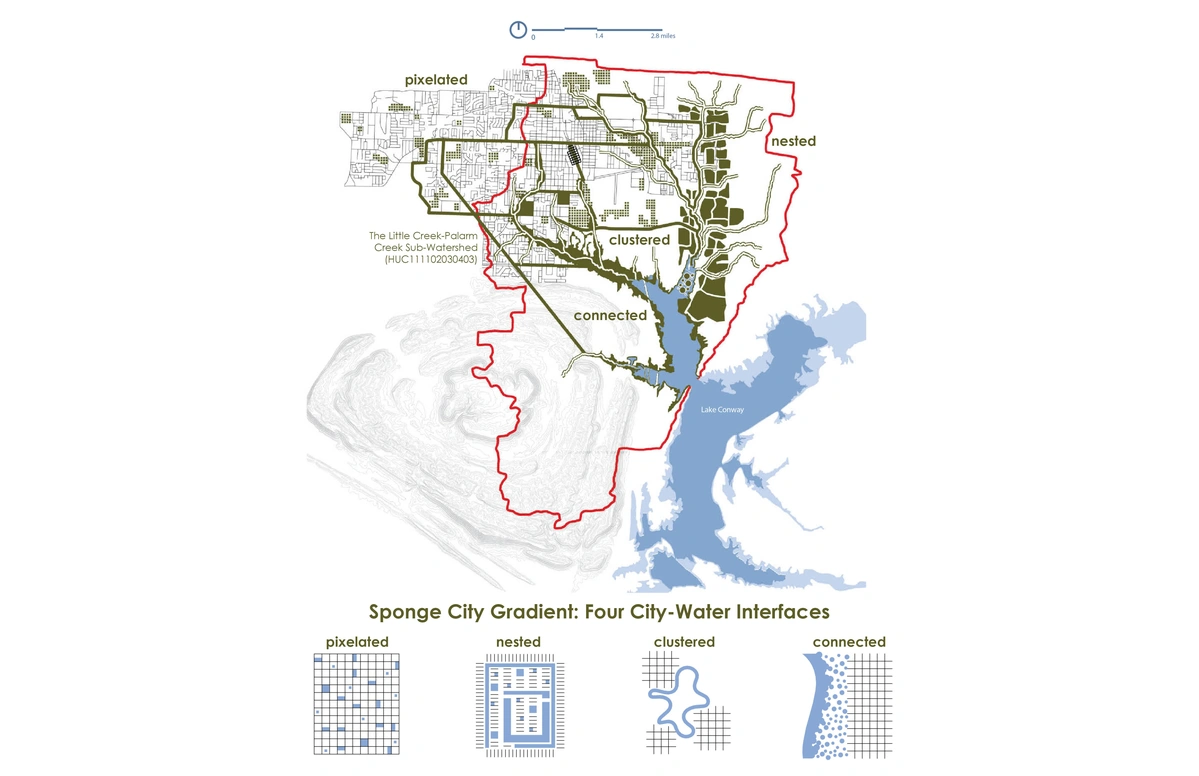

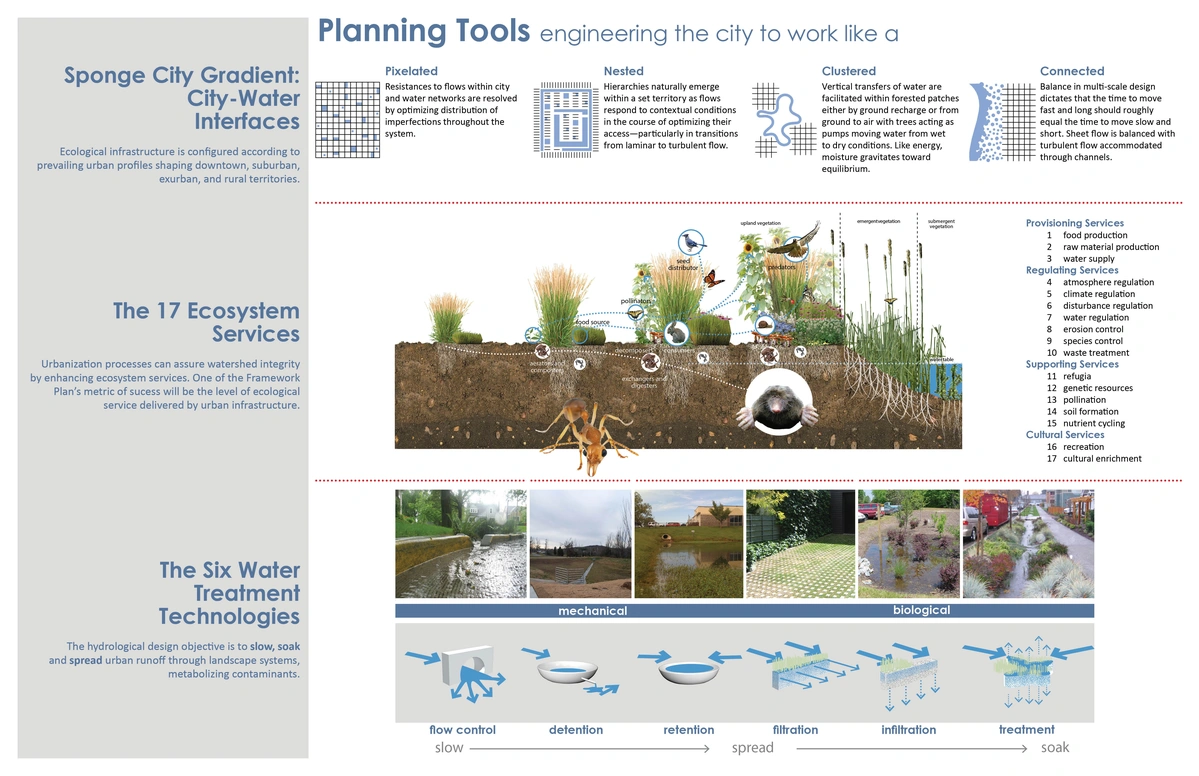

Challenges in implementing resilient design in urban systems include the lack of a common language of assessment and management for the characteristics that makes those systems resilient. Planning tools include a Sponge City Gradient, a Water Treatment Technologies Spectrum, and Six Adaptive Infrastructure Types. Given the limits everywhere in funding, political will, and complexity, the Framework Plan operates evolutionarily through a set of Adaptive Infrastructure Types that are incremental, contextual, and successional. These value-added infrastructural retrofits—green streets, water treatment art parks, urban eco-farms, conservation neighborhoods, parking gardens, riparian corridor improvements, lake aerators, vegetative harvesters and floating bio-mats, and greenways—create gain-of-function abilities in conventional infrastructure. Since watersheds and neighborhoods are energy systems alike, this transferrable technology can be adapted to neighborhood development everywhere.

Urban Watershed. In reconciling two networks—watersheds and cities—flow shifts to diffusion within the neighborhood scale, precisely where the most productive social and biotic interfaces occur.

Planning Tools. Transferable technologies for retrofitting the neighborhood and city to work like a hydrologic filter provide gain-of-function abilities in conventional infrastructure.

High-density Neighborhood. Cities are fragmented; nature is continuous. In land-starved neighborhoods, water treatment facilities are pixelated as bioswales drain to underground filters and basins.

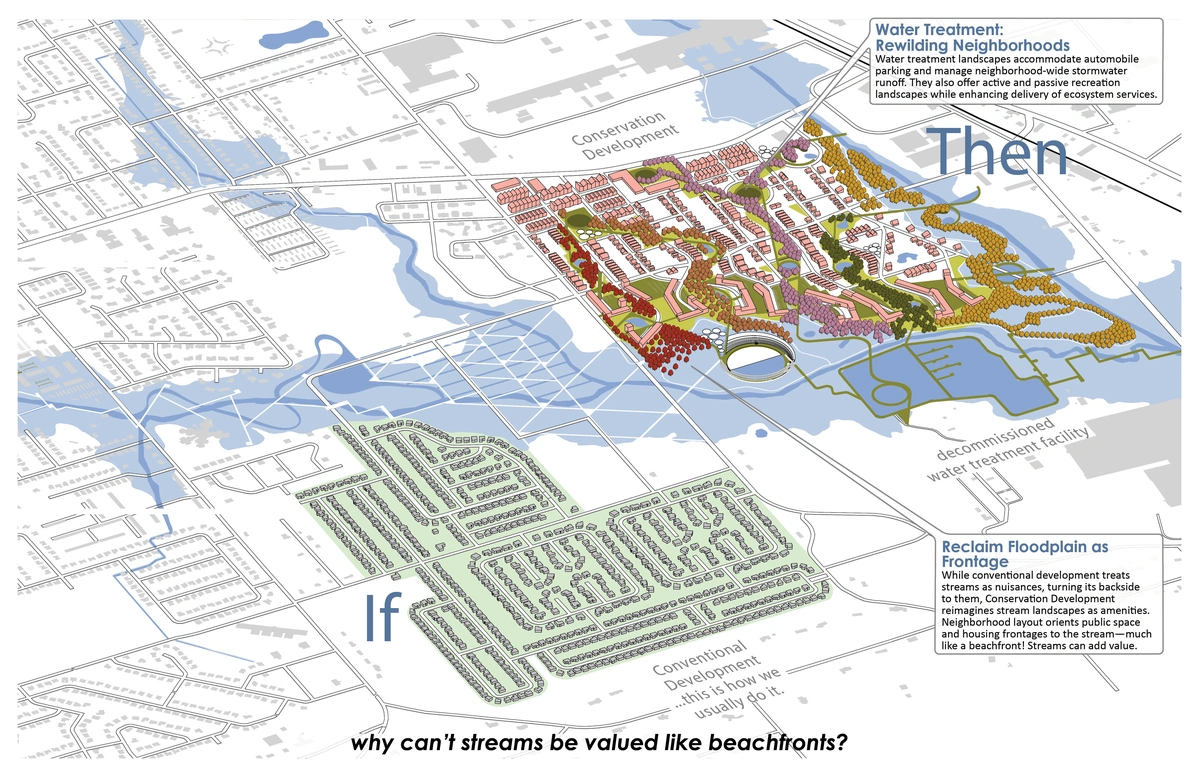

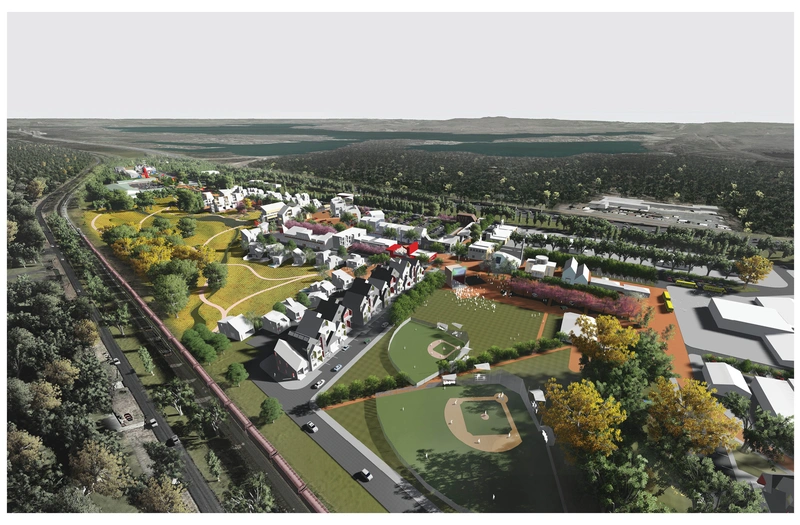

Parks, not Pipes! Conservation development clusters housing to reallocate land for water treatment using soft infrastructure instead of pipes which simply move water problems around.

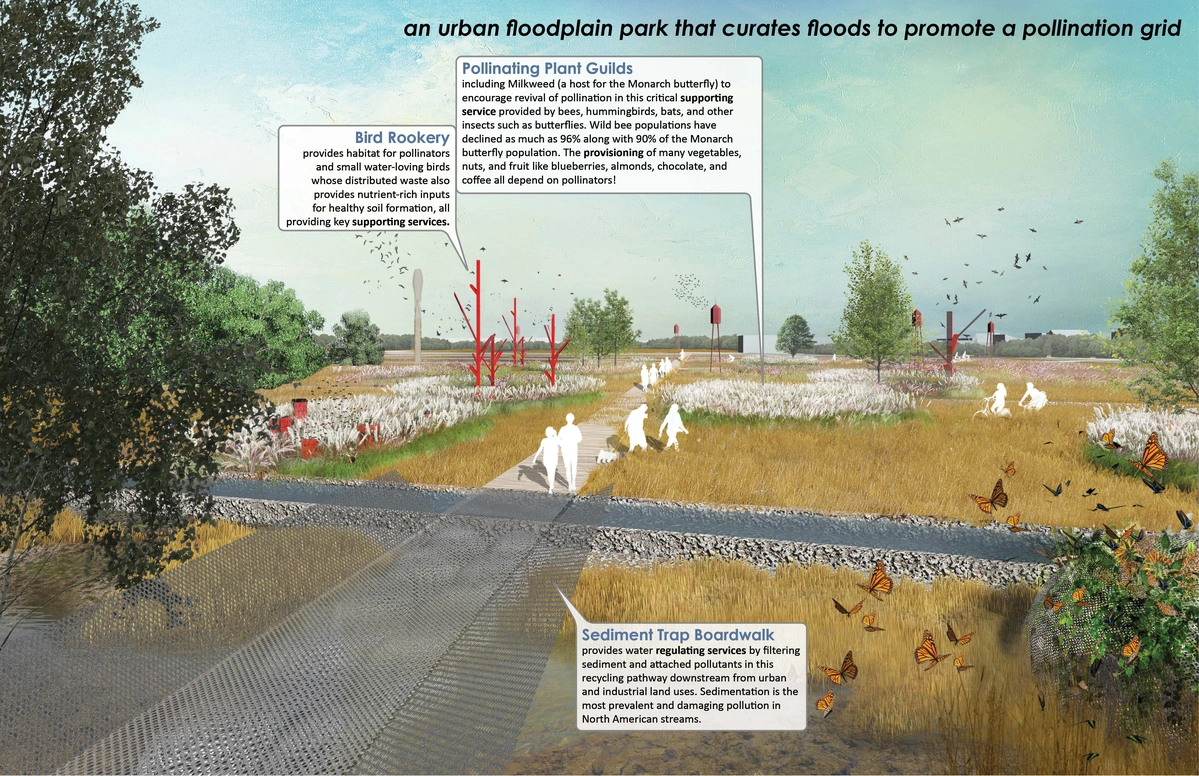

Suburban Neighborhood Wetland. Pulsing water flow is restored in a neglected floodplain to create a pollinator/arts park—the only public amenity for surrounding low-density neighborhoods.

The UACDC is an outreach center of the Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design, and one of a few teaching offices in university-based design programs in the U.S. Staffed by architects, landscape architects, and urban designers, the UACDC’s primary mission is to advance creative development in the physical environment through combined design, research, and educational solutions. Besides traditional associations with engineers and architects, the UACDC sustains deep collaborations with ecological engineers, hydrologists, sociologists, policy analysts, environmental artists, urban economists, food scientists, farmers, and agricultural law professionals. As such, the teaching office facilitates two-way meta-disciplinary work where disciplines internalize the imaginaries and methodologies of another, changing their DNAs.

Building Arkansas’ Best Street: Mayflower, Arkansas: The lamination of a slow street with a highway stretches the civic landscapes and pedestrian spaces common to a town square along Mayflower's 4,500-foot length.

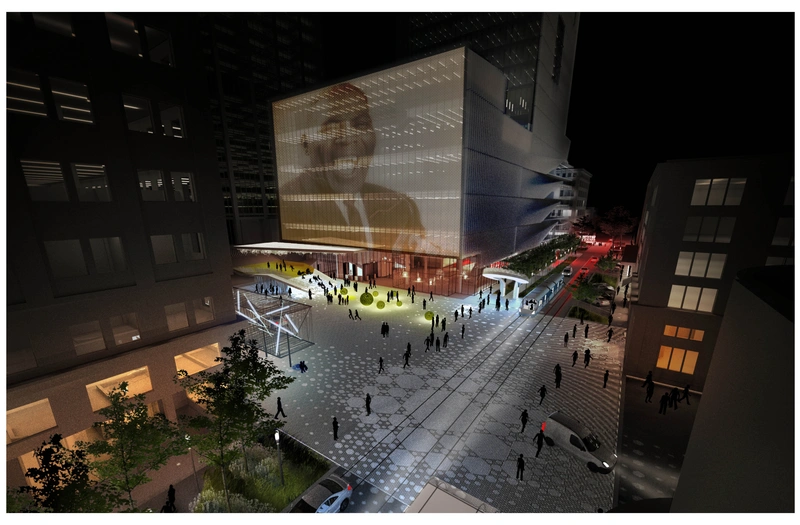

The Creative Corridor: Little Rock, Arkansas: The Creative Corridor retrofits a four-block segment of an endangered historic downtown Main Street through development catalyzed by the cultural arts rather than Main Street’s traditional retail base.

Whitmore Community Food Hub Complex: Wahiawa, Hawai‛i: Community-based food hubs aggregate, process, and distribute product from local growers to wholesale consumers. Not a typical farmer’s market, food hubs incubate resilience through creation of value-added supply chains and a skilled workforce where neither existed. The Food Hub formulates a “missing middle” agricultural infrastructure for community-based food production.