The quality (or desirability) of a neighbourhood is mostly measured in terms of benefices to humans. In this small-scaled project, we work on transforming small lots of neighbourhoods around the Norwegian coastal city of Bergen into beneficial areas for non-humans – with a focus on Møllendal, Kronstad, and Mindemyren. Recuperating the long-established practice of “green guerrilla” and “earth balls”, white cloves start to populate fringes surfaces in these industrial neighbourhoods, creating sweet carpets for honeybees and pollinators to feed on. The site’s utility is thus defined on its contribution to insect health, ensuring a stronger local biodiversity and ecosystem – here neighbourhoods are reconceptualized as inclusive and anti-speciesist, showing that wastelands’ new found usefulness does not need be defined as people-centred.

The connection between Bergen centre and the South suburbs is ongoing change. Road, bike and train infrastructure develop along the industrial axis which follows E-39, the national coastal highway. For decades, the area has been the focus of politicians and urbanists, who oversee its completion as an example of sustainable development. Their language targets the welfare of local populations, with an emphasis on small children and families; it also mentions the “waste land” of the E-39 industrial belt, promising to revitalize it into attractive recreational areas, with shopping and housing. This is a typical long-term project of replacement, where parking lots, delivery zones and run-down boxes are to make way for allegedly exciting and unsoiled architecture; for utile, people-centred neighbourhoods. The intermediary state of affairs, with large construction roads, heavy mineral surfaces, fuelled traffic and cleared weeds, is not supportive of human and animal lives. While the building activities prevent the transformation of small lots along E-39 into spaces that are inhabitable to humans, they don’t prevent their transformation into large pools of food for pollinator insects, whose welfare is strengthened.

Green planning for non-human species in urban areas allows for a renewed perspective on the selection, placement and general management of greens in cities. Critical ways of conceptualizing neighbourhoods should include anti-speciesism – the white clover patches here show us one key example of such critical attitude, as they re-orient “neighbourhood-making” towards more sustainable futures.

Neighbourhoodly spirits are all about cooperation, balanced vivre-ensemble, and mutuality. So, be a good neighbour: if you see some wasteland, unused mineral surfaces, strange corners between houses, plant clovers! Pollinating insects will thrive. It doesn’t matter how small – it makes a difference. And try to limit lawns; cover them with clover, too! The lawn (immaculate, green, well-kept) satisfies humans’ aesthetic desire for tidiness and control over the natural areas that are parts of every neighbourhood. The total area of lawns in Norway is estimated to 100 000 hectares, which corresponds to about 160 000 football pitches; it occupies larger areas than any other type of cultivated land in the country. Yet the lawn offers neither habitat nor food for the natural world – buy yourself some seeds and make sure to change this sterile status. The human-animal community near you will be stronger.

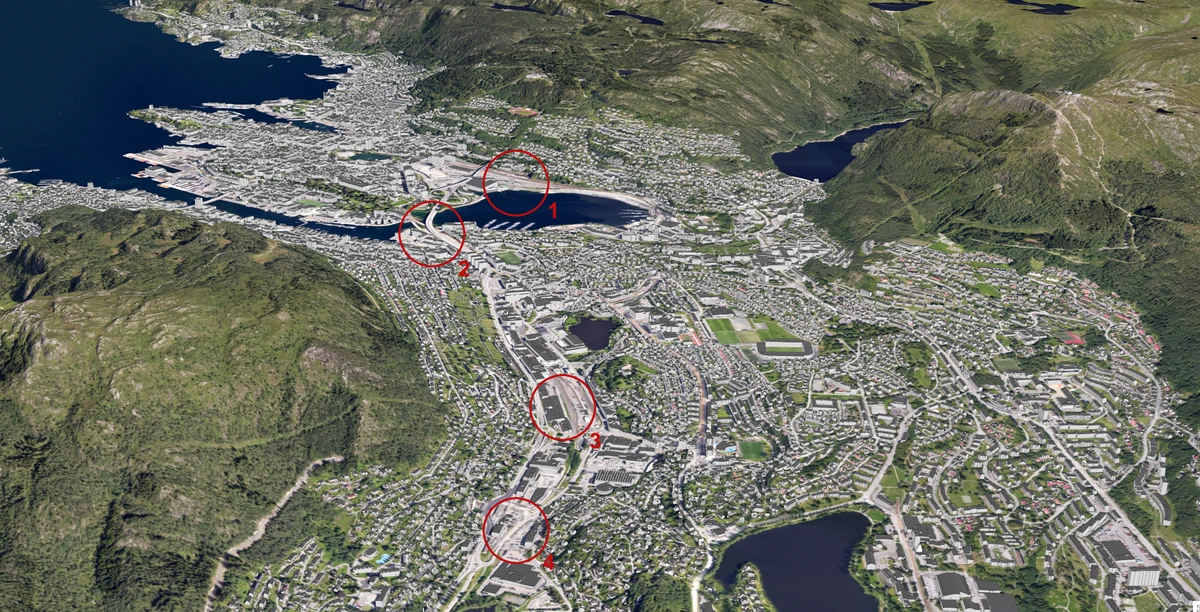

This map shows the different neighborhoods in Bergen that were chosen as sites of intervention (Møllendal, Kronstad, Mindemyren). The E-39 infrastructure is visible in the lower-center portion of the image, and shows the concentration of potential sterile fringes to be pollinated with the white clovers. Many human inhabitants think of the city as green and welcoming, given its location in the mountain ranges, but food for pollinating insects does lack in built areas.

Along the new Bybanen line, many construction works have changed the natural infrastructure of neighbourhoods it crosses. Surfaces that were wild and lush were paved over, decreasing the amount of food available to pollinating insects. As the bike lane follows Bybanen, this site of intervention was quickly covered: white clover seeds were thrown from the pockets as we biked along, planting as a form of temporary repair for pollinators' loss of habitat.

Patches of land around traffic infrastructure like roundabouts, highway passages and other crossings, were planted with sterile grass. We threw punctual seed bombs on these patches, adorning them with new, lush clover flowers; a sugary paradise for bees and other pollinators.

Grass used to cover these "in-between" spaces around Møllendal - now new clover patches make sure that nearby pollinators can find food. Urban wasteland is made useful for non-humans, who get their needed sugars, and, incidentally, it is made more colorful and prettier to the human eye.

Vindfløy Bybigård (founded in 2013) is an apiary and beekeeping project in downtown Bergen, named after the Vindfløy on Mt. Fløyen where the first hives were placed. Beehives are ran from backyards to rooftops in different neighbourhoods all around town, with the aim to engage with different public and local institutions. Vindfløy Bybigård hopes to create awareness for the city as an urban ecosystem, promote biodiversity and support local bees and pollinators by contributing to a more insect- friendly environment in town.

Manuel Hempel (NORCE Research, Climate and Environment Department; University of Bergen, Institute for Geography) is a Bergen-based PhD candidate at NORCE Climate. Manuel works on seasonal forecasting and climate services for sustainable food production within the Norwegian agricultural sector as part of the Climate Futures Centres for Research-based Innovation (funded by the Research Council of Norway). He is the founder of Vindfløy Bybigård.