Extensive multilateral infrastructure investments are changing the city of Nairobi at a tremendous speed, but tend to only favour a small part of the city’s inhabitants. The development is being realized without regard to physical context and worsening the mobility for already vulnerable citizens. The city is developing with two opposing visions: to construct 8-lane highways through the inner city, and to make the city greener and more friendly to non-motorized transport users.

Missing Link 12 is the infrastructural project to connect the main east-west arterials in Nairobi through the informal settlement of Kibera. It comes with a promise of a mobile, blooming and more connected city, but ultimately neglects the disastrous effects of tearing a major residential area in two. Today, the project sits as a 60 m wide void in the centre of Kibera after displacing residents, businesses and schools and continuing to hinder movement within the settlement. The Missing Link 12 project is a clear example of the spatial injustice that is prevalent today in the Global South in general and in Kenya in particular. Large-scale infrastructure projects are built without regard to inhabitants or physical context and worsen the mobility for already vulnerable citizens. The mega project highlights the issue of exclusion and inclusion of various communities, one blocked by a new boundary, a second boosted by high-speed travel.

With this project, I have developed a new strategy for the Missing Link 12 road, exploring how the road could be reprogrammed to better fit the context and the needs of local residents. Working with productive public spaces, flooding prevention and increased mobility.

Architects and urban planners need to learn from the way the street is being used today, especially in the informal settlements, and implement its multifunctionality in the planning of new streets and improvements of existing. The streets were not designed to be markets, playgrounds or someone’s backyard, but are shaped by the people living on the street, adapted by their needs and capacity to claim the public space. It’s a place where both public and private life meet, a space to linger in, and move through at different speed.

The kiosk building becomes a key meeting space to move around and through on the square. A place to buy lunch while waiting for a matatu or bodaboda, to wash your hands after travelling from work and sit in the shade under the large roof.

Small-scale agricultural operations can be a source of income generation and food security, growing popular vegetables as Sukuma wiki, spinage and cabbage.

Strategy 1:1000

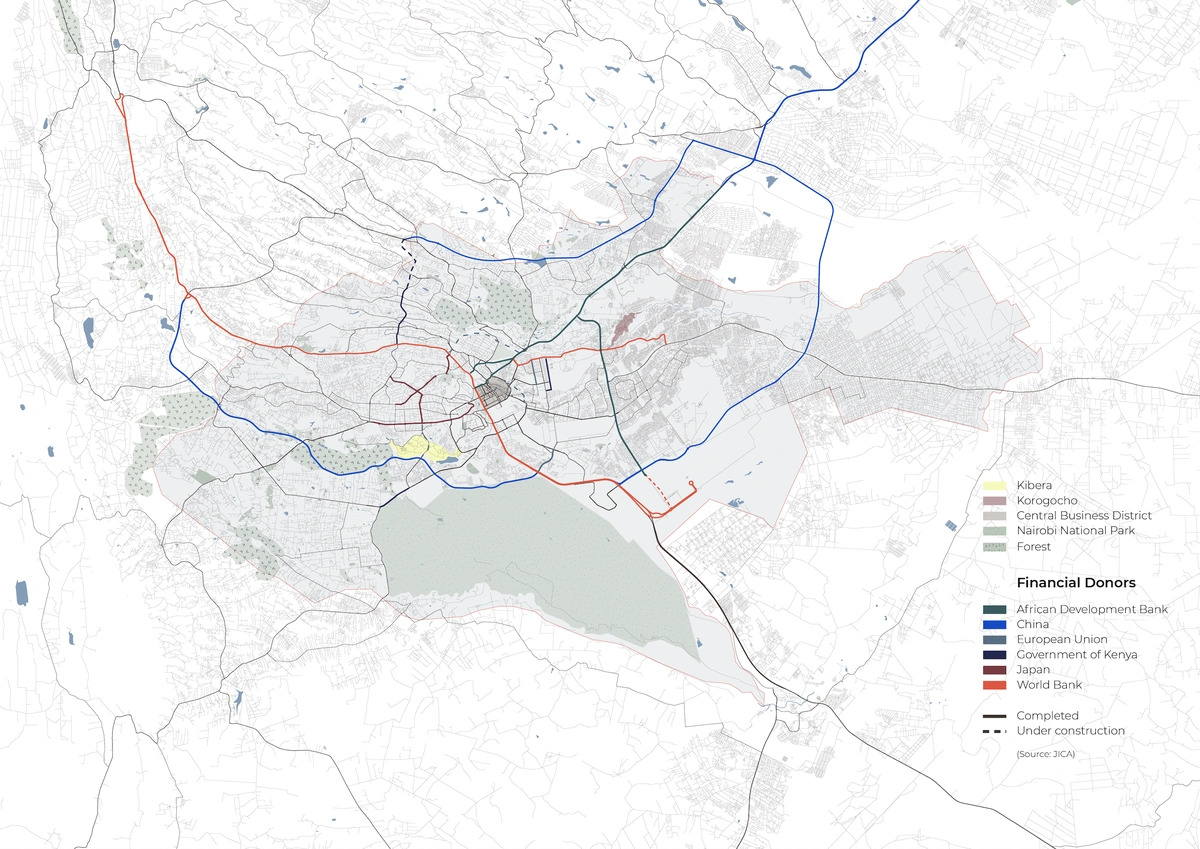

Financial donors of major roads in Nairobi

The sanitation building provides a safe space to use the bathroom, fill up water cans and wash your hands. It extends into the commercial space, with seating to eat a meal bought at the market.

I am an architect and urban planner working at UN-Habitat at the Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme. The project I have submitted was my thesis project from The Royal Danish Academy that I have continued working with, collaborating with Kenyan NGOs and architecture studios.