In this project, we document and examine mechanisms for the division between public and private ownership on the West coast of Norway (Vestlandet), and use them to make sense of discourses and designs of neighbourhoods, with a focus towards the canon notion of “sharing”. Historical and contemporary features of property law, tenure and land division specific to the region, especially to the “klyngetun”, or cluster hamlet, are highlighted through case studies from 3RW’s portfolio. This allows us to reflect back upon our own planning and architecture production.

Six projects realized by the office serve as material examples of changes in property-related perceptions: notions of necessity, commonality, legal redistribution, or private-public management arise and tie themselves to failures and successes of neighbourhoods in Vestlandet. While our exploration is informed by one specific regional (legal and socio-cultural) context, it is understood as a cross-disciplinary model that can benefit conceptualizations and realizations of “neighbourhoods” in and outside Norway.

Sharing land and built infrastructure at the neighbourhood scale is here understood as a constant negociation: the regulatory structures that are put in place as answers to this struggle arise as a key part of how we organize architecture – and our lives. They are tools, complex and diverse, that we should master for the betterment of community building. The different 3RW projects (the Paradis waterfront development, the urban village at Montana, Furuset Hageby, the Nystuveien houses, Grønneviksøren, and the densification plan for Randaberg, all in Vestlandet) are each associated with a specific legal context. We describe how this framework informs private, semi-private and shared amenities in the design.

What does the cluster tun teach us about managing proximities? How does one translate a rule into a space? Can contemporary zoning and bylaws ensure a harmonious vivre-ensemble? How can land division laws fruitfully inform architects and planners’ works? Our work for the creation of good neighborhoods – ones which stimulate interaction, negotiation and other rich sharing practices – cannot simply consist in recreating historical physical forms; it must also address the legal tools that shape its occupants’ life. As tentative responses to such interrogations, the six “architectural neighbourhoods” that feature in our study are like six prototypes for contractual cooperation.

As legal texts and rules, regulatory structures are difficult objects to highlight in architects and planners’ designs – while they are crucial to the good conceptualization and realization of a neighbourhood-scaled project, they generally don’t feature in the project’s presentation and dissemination. To zoom on the mechanisms which regulate the formation and distribution of private and public areas in large housing and planning projects is, in our opinion, a crucial exercise. When commenting on the construction of communities, there’s a lot of talks about the importance of “sharing” – sharing streets, sharing equipment, sharing gardens; sharing values, sharing lifestyle. But how are shared features of neighbourhoods codified and regulated, really? 3RW benefits from an extensive portfolio and has a two-decade-long experience navigating the sinuous regulatory structures of the Norwegian West coast, where most of our architecture was built: we are well positioned to answer that question.

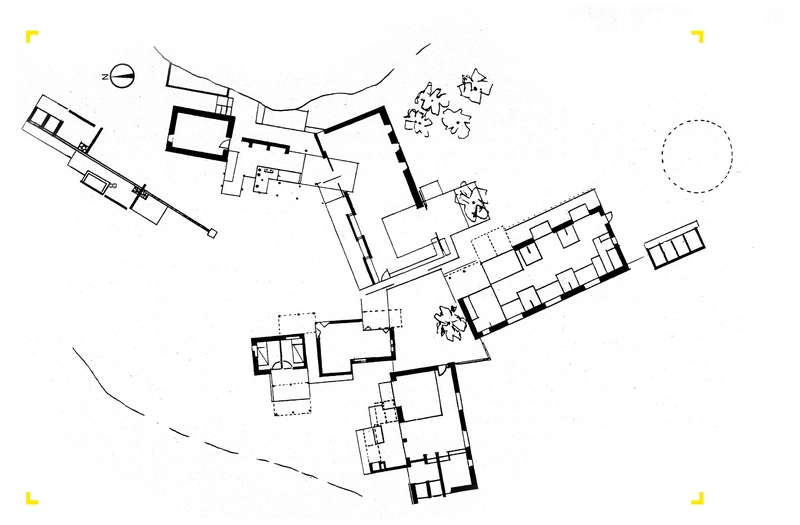

Furuset (3RW, NORD) is a new housing and treatment centre for people with cognitive impairments. It is designed to refer a cluster-like village and community: well-known built elements from residents’ “everyday life” strengthen their sense of autonomy and self. Furuset’s formal and programmatic arrangements reflect that of a small neighbourhood (and not a medical institution) with a variety of public and semi-public spaces and paths, which connect to private dwellings and quieter social areas.

A low-cost building complex made of 727 modules, Grønneviksøren presents many courtyards, shared passages and semi-public galleries, which smoothy lead inhabitants from the vibrant, public ground to their private unit. External galleries have a 3m width, and so are used both as access walkways and common, spacious outdoor areas for social encounters and activities. The inner courtyards are zoned as community outdoor spaces with gardens and playgrounds that serve an appreciable range of users.

Conceived in the context of a feasibility study for the city of Stavanger, this new neighbourhood in Paradis sits on a former railyard, which it occupies with organically distributed volumes. The plan sets ambitious standards for the transformation and densification of vacant land, and features different tenure models for housing, leisure and commerce. Various outdoor spaces are regulated as public or semi-public, insuring a fair access for all to new amenities and the waterfront.

A prototype for the densification of established residential areas, Nystuveien consists of three new homes. The typology suggest that they are detached houses, but they share common foundation, basement, and other built amenities: access to own’s property is reached through shared paths and stairs, creating new proximities between residents. During the design phase, a legal-oriented site analysis led to good, vigorous debates between municipal authorities and the developer.

Sunnhetsgrenden Vardheim healthcare facility (3RW, NORD) is inspired by Norwegian “grend” hamlets, where small clusters of houses create a strongly bonded micro-community: with its clever zoning, mixed ownership and wide-ranging care functions, different relations are set between users and programs. A series of green, public courtyards participate in the welfare of aging residents, and give the facility an important role in animating the small town’s social life.

3RW arkitekter is a Norwegian design practice based in Bergen, with an international team of architects and planners. Since 1999, the practice has handled a wide range of commissions, from national plans for governmental agencies, feasibility studies, environmental impact assessments and masterplans, to housing, infrastructure, landscape, interior architecture and furniture design. It has earned a reputation built on practical experience, socio-cultural work and an award winning creative approach. 3RW arkitekter has retained an important endeavour to participate in the conversation about the role of architecture in society. It has participated extensively in speculative research projects that aim to tackle the agency of architecture in pressing issues of the world. The Triennale team includes employees Tord Bakke (social anthropology), Vilde Kjærsdalen (Vestland housing), Erika Brandl (property rights) and Sixten Rahlff (design direction). Eva Røyrane (“tun” history) is a consultant.

With its tight volumes and steep vertical layout, Lokketune focuses on high utilization of the available land by substituting a single-family home by four dwelling units. This was made possible by a close study and revision of the site’s regulation parameters. Notions of privacy and domestic intimacy are re-negotiated through the project’s set-up, with inhabitants sharing amenities and landscaped outdoor spaces – a mini housing cooperative of sorts, in an area where there is no such culture.

The children’s centre in Chhepetar, Nepal, shows that cluster-inspired organization of zoning and program is a model that transcends the Norwegian context. Different architectural volumes shape an open, in-between space where desirable social encounters and interactions are brought about, and where facility management is eased. A non-profit ownership model informs the movement of different users on site.

The radially-organised educational pavilions in Sabou show that cluster-inspired layouts can benefit programs and users outside of Norway. “Private” classrooms, offices and storage spaces are strategically distributed around a semi-public courtyard, where villagers hold diverse activities after school hours. Stepped areas, as well as informal zoning borders, guide individuals around the educational complex’s many spaces– giving the experience of a smart, self-contained neighbourhood.